By Michele Lynn

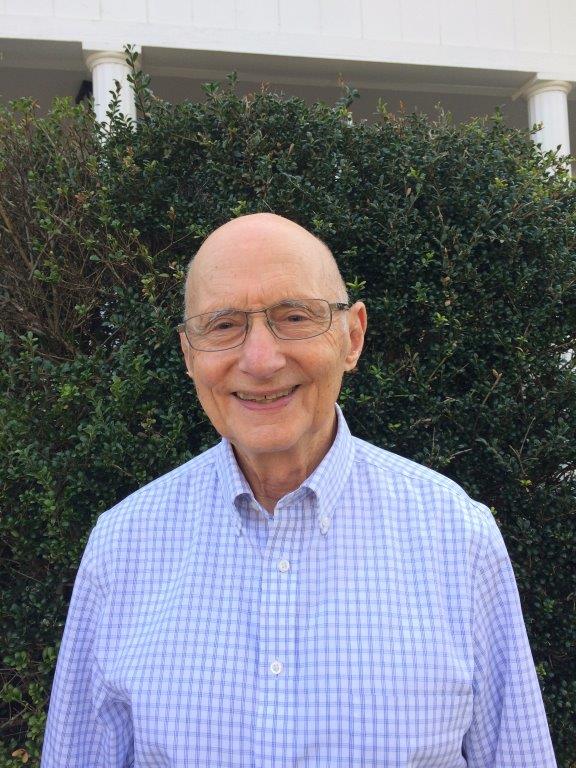

John Rosenberg ’62 was seven years old when the world around him was torn apart. Born and raised in Magdeburg, Germany—an industrial center about 60 miles southeast of Berlin—Rosenberg clearly recalls the events of November 9, 1938, known as Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass. Rosenberg remembers Nazi soldiers forcing him, his then two-year-old brother, and their parents from their apartment, which was next to their synagogue.

“We stood outside while they bombed the inside of the synagogue and we watched it explode,” says Rosenberg. His father, Rudolf, was arrested and taken to the local jail with 125 other Jewish men before being sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp. He spent 17 days there before being released, with the order to leave the country within 30 days.

The family fled to the Netherlands, where they lived in an internment camp for a year before departing on one of the last ships allowed to set sail set for the United States. The family ultimately ended up in Gastonia, NC, where Rosenberg excelled in school, became an Eagle Scout, and went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Duke University in 1953.

Rosenberg served as an officer in the U.S. Air Force for three years in England, becoming friendly with Abe Jenkins, an officer who hailed from South Carolina. After returning a plane to the U.S. from England, the two men boarded a train in New York City to head south to visit their families.

“When the train got to Washington, DC, Jenkins said to me, ‘I’ll see you when we get back to New York,’” says Rosenberg. When Rosenberg asked his fellow uniformed officer, who was Black, where he was headed, he learned that Jenkins needed to move to a train car in the back since they were readying to cross the Mason-Dixon Line. “I grew up in the South so I knew about segregation,” says Rosenberg. “Since the military was the first institution to desegregate, I had served alongside Black men in the Air Force and I was really struck by the injustice.”

While Rosenberg worked for chemical manufacturing company Rohm and Haas Company after the service, he says that he decided to “use his brain” and attend law school. “I initially thought I was going to go back to Gastonia to practice so I wanted to go to the state’s university for my law degree,” he says. Rosenberg was at the UNC School of Law during what he describes as “that wonderful period” when Professors Robert Wettach and Maurice T. Van Hecke—for whom the law school building is named—were teaching. He also relished learning from James Dickson Phillips, Jr., Daniel Pollitt, Henry P. Brandis, Jr.

Julius Chambers, who went on to become a noted civil rights leader, was a classmate and a good friend of Rosenberg’s. That friendship and the Jenkins incident were among the forces that made it clear to Rosenberg that he wanted to devote his career to civil rights work. “I always thought If I could have a small part to play in helping to eliminate this caste system and to create some racial equity, I would feel good about that,” he says.

Rosenberg forged a distinguished career dedicated to human and civil rights, for which he has received myriad awards. From 1962 to 1970, he served as a trial attorney and section chief in the civil rights division of the U.S. Department of Justice where he litigated racial discrimination cases throughout the South. He successfully tried the first case under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and helped prosecute the men responsible for the murder of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman, three civil rights workers killed in Mississippi in 1964.

In 1970, Rosenberg and his wife, Jean, were ready for a change of pace so they left DC with their three-month-old son to go on a camping trip through the Northeastern United States and Canada. While away, they learned about an opportunity in the coalfields area of eastern Kentucky to examine the legal and structural issues of poverty in the region and the health and safety issues coal miners were facing. “We thought that this would be a good thing to do for a couple of years and that was more than 50 years ago,” Rosenberg says with a laugh.

They moved to Prestonsburg, KY where Rosenberg organized the Appalachian Research and Defense Fund of Kentucky, Inc. (AppalReD), a nonprofit law firm providing free civil legal help to eligible low-income people in 37 counties of the Appalachian Mountains and hills of eastern and south-central Kentucky. Funded by public and private grants and donations, AppalReD staff initially focused on environmental and safety issues related to coal mining. Facing a poverty population of more than 240,000 people in a 37-county area, they quickly expanded their work to include representation in the traditional areas of poverty law: consumer, social security, and housing, family law and other issues that those in poverty face.

“I’m proud of starting this legal services agency that is now past its 50th year in providing excellent representation for low-income people in Kentucky,” he says. Rosenberg was also the driving force behind the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center (ACLC), a nonprofit law firm in Whitesburg, KY, now in its 20th year. ACLC has taken over AppalReD’s coal-related work, so that the AppalReD staff can concentrate on traditional poverty issues.

“I’m proud of starting this legal services agency that is now past its 50th year in providing excellent representation for low-income people in Kentucky,”

John Rosenberg ’62

While he retired 20 years ago, Rosenberg remains extremely involved in his community. “At this young age (of 90), I’m still involved with the American Bar Association, where I serve on the pro bono committee,” he says. He is active with the Kentucky State Bar Association, acts as vice chair of the Floyd County Community Foundation, and is the longest-serving member of the Kentucky Public Advocacy Commission, which oversees the Kentucky Public Defender System. Since 1994, Rosenberg has been reappointed to the commission by a number of governors from both the Republican and Democratic parties.

As if that were not enough, he is an advisor to a local private school that serves low-income students and also advises local nonprofits on legal issues. He is of counsel to a local law firm, where he specializes in environmental issues and representing the elderly. He also talks about his Holocaust experience with local high school classes.

When asked what inspires his activism, Rosenberg mentions tikkun olam, a concept in Judaism defined by performing various actions to repair the world. “I am fortunate and truly blessed to be healthy at this age and I want to still be productive and help folks and as much as I can,” he says. “It’s been a privilege to have a career in public service, and I encourage young lawyers to consider it. Public service is a way of helping folks who otherwise wouldn’t have lawyers. And it’s important in this country, under the rule of law, for all people to have legal representation.”